Cross Cultural Communication

As we work remotely more than ever before, both because of COVID19 and because of how our work world has shrunk with the usage of collaboration tools, we must remember our differences and adapt to one another.

Yesterday I had a wonderful perspective shown to me that I have rarely needed to contemplate. I am used to working for companies headquartered in the US, so my offshore teams and teammates reported up through me and were responsible for meeting goals that I had given them. But the development manager I spoke with worked for a large foreign multinational and reminded me of how the subsidiary he worked for, itself headquartered in the US, actually had to march to a different kind of beat – in fact, they had to adapt to goals and leadership from a different culture. The type of mentality required when working with this type of organization is much different than the “fail fast” and “be bold” ethos of so many of our domestic tech organizations. And more than that, it made me think of how much parsing, translating, and nuance are required when communicating with our cross-cultural teams.

There is nothing negative about this. Indeed, the “new normal” is that as our world continues to mature, we will be communicating with different cultures much more often than our parents would have thought possible. It means that in addition to understanding the messages and ideas that we are passing back and forth we must also understand the perspectives that these communications are derived from.

In short, communication theory is as important now as ever. Let us look at it briefly and then dive into what it means cross-culturally.

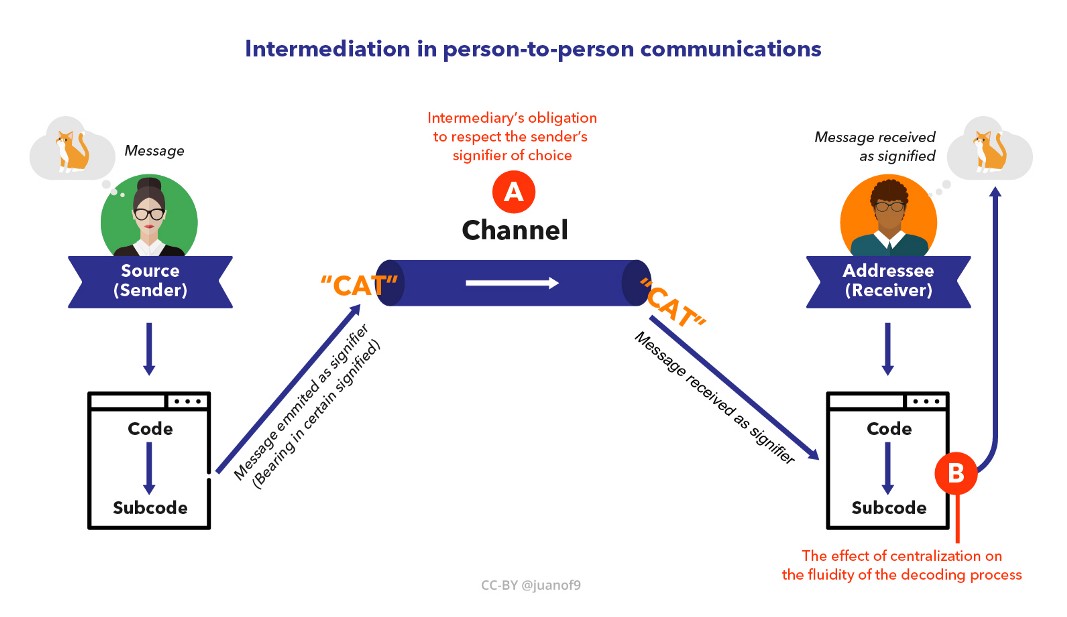

JuanOF9 / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

Briefly, communication theory tells us that the exchange of ideas – such as “cat” – actually consists of a number of steps that each, much like a game of telephone, slightly modify the idea being exchanged. For starters, the concept of a cat needs to be filtered through the “sender’s” experiences and knowledge. By doing so, the sender “encodes” the idea of a cat into a message that can be communicated, such as “I have bought a cat”. It is in English, it is a grammatically correct sentence, and it has verb/subject/object agreement.

From here we have the beginnings of a change from the idea of “cat”. Perhaps the sender is planning on talking about cat allergies, for example, and is framing up the conversation. The potential misunderstandings do not end, for next the sender must actually transmit the message to the receiver. Perhaps it is over email or via voice, but what if there is static, or an individual is deaf or blind, or a spam blocker blocks the email? The communication channel might even be other people, like an actual game of telephone, and the message could be changed when it is received.

Once the message is received, it must be “decoded” by the receiver and filtered through their own experiences and knowledge. While the idea of “cat” is highly likely to be understood, perhaps the idea of “axolotl” or “durian fruit”, for example, might be completely filtered out during decoding and the receiver would have absolutely no idea of what the sender is trying to communicate. In any event, it is only now that the initial idea of “cat” is being processed by the receiver.

When it comes to remote cross-cultural communication, the life experiences between the sender and receiver are significantly different, and the communication channel often disallows non-verbal communication such as inflection, body-language, etc. Step 1 of any attempt to improve one’s cross-cultural communication must necessarily start with an understanding of the existence of these differences. Allow for misunderstandings to occur and react in the same kind of spirit, where the wrong words and concepts may be unintentionally communicated. And keep in mind that with English as the lingua franca, it is highly likely your communication partner(s) are translating every word.

Step 2 is understanding a bit more about large cultural phenomenon. One such is the idea of “independent” and “interdependent” cultures. In the USA, we are an “independent” culture, as is much of the western world. We expect initiative and boldness and reward independent action, and we value personal responsibility. Yet, the majority of the world’s population tends to be a part of “interdependent” cultures, where strong family connections, a deference to authority, and a bias towards consensus means slower decision making, more thought before action, but also more sacrifice for and commitment to the team.

Indeed, we citizens of independent cultures must contemplate how messages from interdependent cultures are being encoded. We must interpret whether it is a message from an individual, reflecting actual thoughts and beliefs, or whether it is a team-driven communication so that the sender is not rocking the boat. We must also allow for messages to be highly nuanced and, frankly, off-base, so that the sender can defer to authority or save face. In doing so, we may be able to get to the truth of the message rapidly, and we can again allow for some misunderstandings related to the decoding process and defuse potential situations caused by, for example, face saving.

Another relatively recent breakthrough is the identification of “Ask” vs “Guess” culture. Some individuals are open about certain needs, regardless of tact or propriety – asking for raises, for example, or if someone would like to join a certain project. In our western male-dominated workplace this is often the default mode of communicating needs. However, there is a significantly adherents to “guess” culture, where probing and tact take center stage. Indeed, someone from “guess” culture is perhaps feeling out their boss, getting hints on performance and mentioning stellar reviews, instead of coming right out and asking for a raise.

Step 3 towards strong cross-cultural communication is recognizing when someone is an “asker” and a “guesser”. This often means working with an asker’s requests and demands with emotional stillness, recognizing that they are forthright and open, and refusing to be swayed or angered by the approach. It also means understanding when someone is a “guesser”, in order to move the requested conversation forward and head towards mutual understanding.

Lastly, let us touch upon unconscious bias. As well as being a thorn in any hiring manager’s side, unconscious bias can affect our approach to cross-cultural communication by influencing how we are decoding a message. One very tangible example is the accent – we have preconceived notions about each other’s intelligence and tact based simply on how we sound, not even considering the words we use. But more than that, unconscious bias causes us to have inappropriate reactions to the ways that other cultures encode their messages. Many cultures in the EMEA region of the world are heavily male-dominated, and message encoding will come from such a perspective. If we want to work with individuals in this part of the world as equals, we need to keep in mind this perspective and allow for this difference. Step 4 is therefore to be aware of your unconscious bias and how it might impact how you decode / interpret communications from other cultures.

Putting it all together, it is apparent that a major part of cross-cultural communication is openness, tolerance, and patience. We must allow for communications to need updating and clarification, and we must also be aware of how other cultures are encoding their messages. By improving our understanding of communication itself, of large cultural phenomena, and compensating for our unconscious biases, we can greatly improve how we communicate cross-culturally, leading to faster responses, quicker understandings, and improved quality.